While working on my toy software rasterizer, at some point I decided to try rendering a skybox using cube maps. Loading and drawing a pre-existing environment cube map as 12 triangles proved to be easy and boring. Next, I looked into generating the skybox programmatically on the fly during each frame. The first attempt used the Preetham daylight model. It worked, but I couldn’t tune it well enough to produce good-looking results for a dynamic sky with the Sun moving in real time from dawn till dusk. This paper explores the issues well: “A Critical Review of the Preetham Skylight Model”. Next attempt used the Hosek-Wilkie sky model (paper, presentation), which produced much more convincing results.

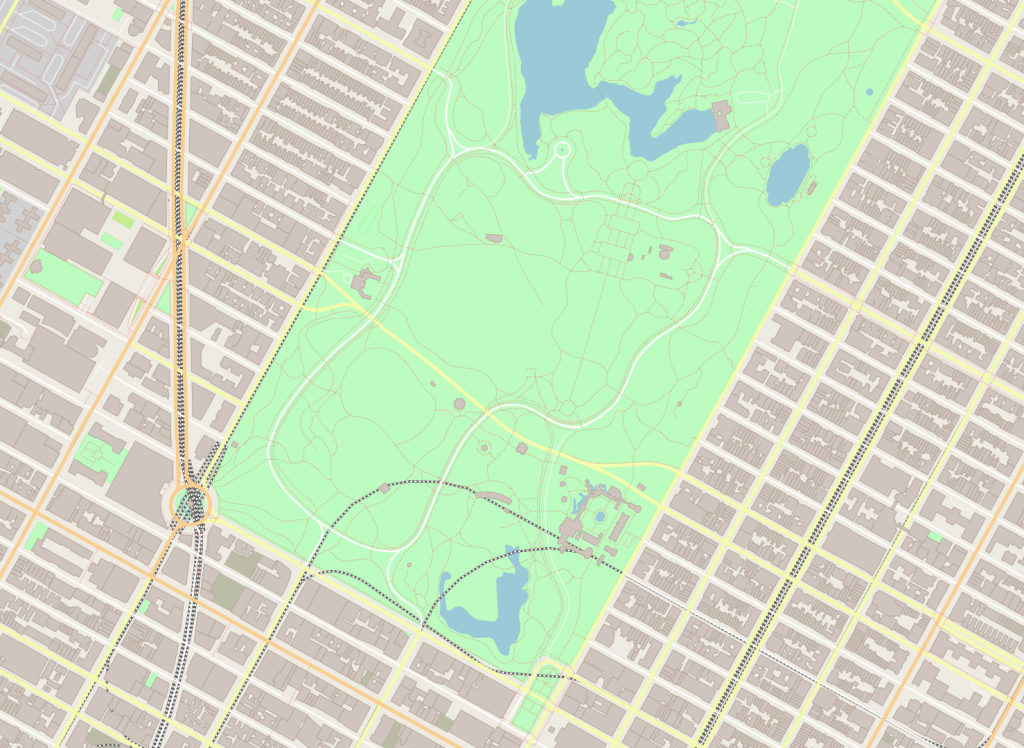

This model allows sampling sky radiance to build an image like this:

When combined with a visualization of a moving Sun and rendered for five cube-map faces each frame, it results in a lively sky background like this:

This video shows the Skybox example from the NIH2 software renderer, which runs at ~150 FPS at 720p on an Apple M1 CPU.

This blogpost summarizes the experience of running the Hosek-Wilkie sky model on the CPU and iteratively optimizing the implementation enough for semi real-time use cases. It also provides a distilled version of the source code detached from the software renderer. The code is written in Rust, but this doesn’t matter much, as the logic behind the optimizations is equally applicable to any compiled language.

For simplicity, the implementation builds only a single cube-map face (negative Z). Since the sky model is defined only for Sun directions with Y>=0, only the top half of this face is filled. Extending the logic for other faces is pretty straightforward, but makes the code hairier, so they were omitted.

The optimizations focus on single-threaded performance, as building multiple faces can be trivially parallelized across threads. A resolution of 1024×512 was chosen for benchmarking each iteration of the code, measurements were done on the base Apple M1 CPU.

V0 – Initial implementation

The sky model has two kinds of inputs:

-

- Per entire sky dome (during model initialization):

- Turbidity [1..10] – measure of aerosol content in the air

- Ground albedo [0..1 x 3] – fraction of sunlight reflected by the ground

- Solar elevation [0°..90°] – how high the Sun is

- Per view direction (during sampling):

- Theta θ [0°..90°] – view angle from the zenith

- Gamma γ [0°..180°] – angle between the view direction and the Sun

- Per entire sky dome (during model initialization):

Conceptually, building a single cube-map face consists of the following steps:

-

- Initialize the sky model (can be shared across faces)

- For each pixel on the face:

- Compute θ and γ

- Sample the model with (θ, γ) three times (once per RGB channel)

- Tone-map, convert to sRGB, and write out as U8 x 3

Sky model initialization is performed once per frame and is very cheap. It mainly consists of evaluating equation (11) a few times on the table data and lerping between the results.

θ and γ are computed from pixel coordinates (x, y) as follows:

let u: f32 = 2.0 * (x as f32 + 0.5) / (width as f32) - 1.0; // [-1, 1]

let v: f32 = ((height - 1 - y) as f32 + 0.5) / (height as f32); // [0, 1]

let dir: Vec3 = Vec3::new(u, v, -1.0).normalize(); // ZNeg => Z=-1

let theta: f32 = dir.y.acos(); // view angle from zenith

let cos_gamma: f32 = dir.dot(sun_direction);

let gamma: f32 = cos_gamma.acos(); // angle between view direction and sun

Sampling the model is done by implementing the equations (8, 9) directly:

pub fn f(&self, theta: f32, gamma: f32) -> (f32, f32, f32) {

let chi = |g: f32, a: f32| -> f32 {

let num: f32 = 1.0 + a.cos().powi(2);

let denom: f32 = (1.0 + g.powi(2) - 2.0 * g * a.cos()).powf(3.0 / 2.0);

num / denom

};

let eval = |p: [f32; 9], theta: f32, gamma: f32| -> f32 {

let a: f32 = p[0];

// ...

let i: f32 = p[8];

let term1: f32 = 1.0 + a * (b / (theta.cos() + 0.01)).exp();

let term2: f32 = c + d * (e * gamma).exp() + f * gamma.cos().powi(2) +

g * chi(i, gamma) + h * theta.cos().sqrt();

term1 * term2

};

let f0: f32 = eval(self.distribution[0], theta, gamma);

let f1: f32 = eval(self.distribution[1], theta, gamma);

let f2: f32 = eval(self.distribution[2], theta, gamma);

(f0 * self.radiance[0], f1 * self.radiance[1], f2 * self.radiance[2])

}

For tone mapping I used Reinhard since it’s simple and robust. Gamma correction and clamping are applied before writing out a pixel:

// ...

let f: (f32, f32, f32) = sky.f(theta, gamma); // sample the radiance

let c: (f32, f32, f32) = linear_to_rgb(f); // convert to display sRGB space

// Write out as u8 RGB

let idx: usize = y * width + x; // pixel index

pixels[idx * 3 + 0] = (c.0 * 255.0).clamp(0.0, 255.0) as u8;

pixels[idx * 3 + 1] = (c.1 * 255.0).clamp(0.0, 255.0) as u8;

pixels[idx * 3 + 2] = (c.2 * 255.0).clamp(0.0, 255.0) as u8;

// ...

fn to_srgb(c: (f32, f32, f32)) -> (f32, f32, f32) {

let encode = |x: f32| {

if x <= 0.0031308 {

12.92 * x

} else {

1.055 * x.powf(1.0 / 2.4) - 0.055

}

};

(encode(c.0), encode(c.1), encode(c.2))

}

fn tonemap_reinhard(rgb: (f32, f32, f32), exposure: f32, white: f32) ->

(f32, f32, f32) {

let r: f32 = rgb.0 * exposure;

let g: f32 = rgb.1 * exposure;

let b: f32 = rgb.2 * exposure;

let y: f32 = 0.2126 * r + 0.7152 * g + 0.0722 * b;

let s: f32 = (1.0 + y / (white * white)) / (1.0 + y);

(r * s, g * s, b * s)

}

fn linear_to_rgb(c: (f32, f32, f32)) -> (f32, f32, f32) {

let exposure: f32 = 0.5;

let white_point: f32 = 14.0;

let exposed: (f32, f32, f32) = tonemap_reinhard(c, exposure, white_point);

let display: (f32, f32, f32) = to_srgb(exposed);

display

}

Result: this version works, but it takes ~46ms to build a single face. Too slow…

V1 – Less wasteful computation

The amount of work the poor old scalar CPU has to perform per pixel is no joke. Worse still, compilers (including rustc) are constrained by strict IEEE floating-point semantics, which prevents many otherwise valid optimizations. However, it is possible to manually simplify parts of the formulas and hoist redundant computations:

-

cos(θ)andcos(γ)are already available, there’s no need to re-calculate them again inside the function bodyv.powf(3.0 / 2.0)is mathematically equivalent tov * v.sqrt(), which is much cheaperv.powi(2)is equivalent tov * v, in case the compiler fails to expand it

Result: these simple transformations reduce the compute time down to ~28ms.

V2 – Per-pixel SIMD

Staring at this snippet for long enough:

let f0: f32 = eval(self.distribution[0]);

let f1: f32 = eval(self.distribution[1]);

let f2: f32 = eval(self.distribution[2]);… eventually raises the question – since we’re doing the same computation three times, just with different input data, why not do all three in parallel?

Of course, there are no SIMD registers with three lanes, but nothing prevents from using a fourth throwaway lane for free. Effectively, running the formulas (8, 9) for RGBX, where the distribution and radiance values for the fourth lane are zeroed out.

A direct translation of the sampling function to 4-way SIMD looks like this:

pub fn f(&self, theta: f32, gamma: f32, theta_cos: f32, gamma_cos: f32) -> (f32, f32, f32) {

let a: F32x4 = F32x4::load(self.distribution4[0]);

...

let i: F32x4 = F32x4::load(self.distribution4[8]);

let one: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(1.0);

let two: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(2.0);

let zero_zero_one: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(0.01);

let gamma: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(gamma);

let theta_cos: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(theta_cos);

let gamma_cos: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(gamma_cos);

let radiance: F32x4 = F32x4::load(self.radiance4);

let term1: F32x4 = (b / (theta_cos + zero_zero_one)).exp() * a + one;

let chi_num: F32x4 = one + gamma_cos * gamma_cos;

let chi_denom: F32x4 = one + i * (i - gamma_cos * two);

let chi: F32x4 = chi_num / (chi_denom * chi_denom.sqrt());

let term2: F32x4 = c + d * (e * gamma).exp() + f * gamma_cos * gamma_cos +

g * chi + h * theta_cos.sqrt();

let c: F32x4 = (term1 * term2) * radiance;

let c4: [f32; 4] = c.store();

(c4[0], c4[1], c4[2])

}

Here I use a custom F32x4 SIMD type that provides trig and pow/exp/log operations, but really any decent SIMD library would do. I’m mostly using ARM64, but also want the code to run on AMD64, so a 4-wide type is the common denominator.

Result: this version takes the previous ~28ms down to ~26ms. Meh, rather underwhelming. It clearly demonstrates a well-known truth – effective SIMD requires rethinking both data layout and function interfaces. Otherwise, the ceremony of setting up SIMD computation and getting the results back nullifies any gains from the parallel compute.

V3 – Per-row SIMD

The next step was to go into full SIMD. Drop the per-pixel approach entirely and instead perform the computation per rows, separately for the R, G, and B channels. With width=1024, this means first writing out (cos(θ), γ, cos(γ)) for the entire row (1024 x 3 x 4b = 12Kb), and then calculating the formulas (8, 9) from the paper and writing them into three output arrays (1024 x 3 x 4b = 12Kb). Since the size of the scratchpad arrays is about 24Kb, the CPU should rarely touch memory outside the L1 cache:

// Per-row scratch space

let mut theta_cos_row: Vec<f32> = vec![0.0; width];

let mut gamma_cos_row: Vec<f32> = vec![0.0; width];

let mut gamma_row: Vec<f32> = vec![0.0; width];

let mut r_row: Vec<f32> = vec![0.0; width];

let mut g_row: Vec<f32> = vec![0.0; width];

let mut b_row: Vec<f32> = vec![0.0; width];

//...

// Calculate radiance per each channel, entire row at a time

sky.f_simd_r(&gamma_row, &theta_cos_row, &gamma_cos_row, &mut r_row);

sky.f_simd_g(&gamma_row, &theta_cos_row, &gamma_cos_row, &mut g_row);

sky.f_simd_b(&gamma_row, &theta_cos_row, &gamma_cos_row, &mut b_row);The function interface changes accordingly – it now accepts spans of input arrays and a span of an output array. The internal logic remains the same, but it operates on chunks of 4 input values, passing them through the transformation and writing out 4 results per iteration:

fn f_simd_channel<const CHANNEL: usize>(

&self,

gamma: &[f32],

theta_cos: &[f32],

gamma_cos: &[f32],

output: &mut [f32]) {

let gamma: *const f32 = gamma.as_ptr();

let theta_cos: *const f32 = theta_cos.as_ptr();

let gamma_cos: *const f32 = gamma_cos.as_ptr();

let output: *mut f32 = output.as_mut_ptr();

let a: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(self.distribution[CHANNEL][0]);

// ...

let i: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(self.distribution[CHANNEL][8]);

let one: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(1.0);

let two: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(2.0);

let zero_zero_one: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(0.01);

let radiance: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(self.radiance[CHANNEL]);

for idx in (0..=len - 4).step_by(4) {

let gamma: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe {*(gamma.add(idx) as *const [f32; 4])});

let theta_cos: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe {*(theta_cos.add(idx) as *const [f32; 4])});

let gamma_cos: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe {*(gamma_cos.add(idx) as *const [f32; 4])});

let term1: F32x4 = (b / (theta_cos + zero_zero_one)).exp() * a + one;

let chi_num: F32x4 = one + gamma_cos * gamma_cos;

let chi_denom: F32x4 = one + i * (i - gamma_cos * two);

let chi: F32x4 = chi_num / (chi_denom * chi_denom.sqrt());

let term2: F32x4 = c + d * (e * gamma).exp() + f * gamma_cos * gamma_cos + g * chi + h * theta_cos.sqrt();

let c: F32x4 = (term1 * term2) * radiance;

c.store_to(unsafe { &mut *(output.add(idx) as *mut [f32; 4]) });

}

}Result: this data-layout transformation cuts the runtime from ~26ms to ~13ms. In other words, it is twice as fast while conceptually doing more work in the process, since inputs and outputs are first written to scratch arrays instead of being consumed immediately one by one.

V4 – FMA and raw pointer arithmetic

Now that the implementation operates in SIMD intrinsics, it becomes possible to save a few more instructions by using fused multiply-add (FMA) where applicable. The assembly listing also showed some unnecessary checks around loop iteration and pointer arithmetic; this can be fixed by re-writing the code to be as primitive as possible:

fn f_simd_channel<const CHANNEL: usize>(

&self,

gamma: &[f32],

theta_cos: &[f32],

gamma_cos: &[f32],

output: &mut [f32]) {

let mut gamma_ptr: *const f32 = gamma.as_ptr();

let mut theta_cos_ptr: *const f32 = theta_cos.as_ptr();

let mut gamma_cos_ptr: *const f32 = gamma_cos.as_ptr();

let mut output_ptr: *mut f32 = output.as_mut_ptr();

let a: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(self.distribution[CHANNEL][0]);

// ...

let i: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(self.distribution[CHANNEL][8]);

let one: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(1.0);

let minus_two: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(-2.0);

let zero_zero_one: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(0.01);

let radiance: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(self.radiance[CHANNEL]);

let steps: usize = len / 4;

for _idx in 0..steps {

let gamma: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe { *(gamma_ptr as *const [f32; 4]) });

let theta_cos: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe { *(theta_cos_ptr as *const [f32; 4]) });

let gamma_cos: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe { *(gamma_cos_ptr as *const [f32; 4]) });

let term1: F32x4 = (b / (theta_cos + zero_zero_one)).exp().fma(a, one);

let chi_num: F32x4 = gamma_cos.fma(gamma_cos, one);

let chi_denom: F32x4 = gamma_cos.fma(minus_two, i).fma(i, one);

let chi: F32x4 = chi_num / (chi_denom * chi_denom.sqrt());

let term2: F32x4 = theta_cos

.sqrt()

.fma(h, (f * gamma_cos).fma(gamma_cos, g.fma(chi, (e * gamma).exp().fma(d, c))));

let channel_radiance: F32x4 = (term1 * term2) * radiance;

channel_radiance.store_to(unsafe { &mut *(output_ptr as *mut [f32; 4]) });

gamma_ptr = unsafe { gamma_ptr.add(4) };

theta_cos_ptr = unsafe { theta_cos_ptr.add(4) };

gamma_cos_ptr = unsafe { gamma_cos_ptr.add(4) };

output_ptr = unsafe { output_ptr.add(4) };

}

}With these changes, the core of the implementation turns into a large loop with one conditional jump. The assembly output becomes a wall of branchless 4-wide vector operations, beautiful!

Result: these tweaks shave off another ~1ms from the runtime, bringing it down to ~12ms.

V5 – Computing theta and gamma with SIMD

At this point there are no more low-hanging fruits in the Hosek-Wilkie sky sampling itself; the scaffolding around it became the bottleneck instead. The calculation of theta and gamma, while not super expensive, can still be accelerated by deriving 4 triplets at a time. Instead of recalculating (u, v) from (x, y) per-pixel, the initial direction vector and the dX/dY stepping constants are computed once. Next, updating the direction component, while stepping through 4 values, is then done via a single add instruction:

for x in (0..width).step_by(4) {

// normalize the components of the direction vector

let recip_len_sqrt: F32x4 = vec_x_4.fma(vec_x_4, vec_y2_z2_4).rsqrt();

let normalized_vec_x_4: F32x4 = vec_x_4 * recip_len_sqrt;

let normalized_vec_y_4: F32x4 = vec_y_4 * recip_len_sqrt;

let normalized_vec_z_4: F32x4 = vec_z_4 * recip_len_sqrt;

// cos(theta) - cos(angle between the zenith and the view direction)

let theta_cos_4: F32x4 = normalized_vec_y_4;

// gamma_cos = dot(dir, sun_dir).clamp(-1.0, 1.0);

let gamma_cos_4: F32x4 = (normalized_vec_x_4 * sun_dir_x_4

+ normalized_vec_y_4 * sun_dir_y_4

+ normalized_vec_z_4 * sun_dir_z_4)

.min(F32x4::splat(1.0))

.max(F32x4::splat(-1.0));

// gamma - angle between the view direction and the Sun

let gamma_4: F32x4 = gamma_cos_4.acos();

theta_cos_4.store_to(unsafe {&mut *(theta_cos_row.as_mut_ptr().add(x) as *mut [f32; 4])});

gamma_cos_4.store_to(unsafe {&mut *(gamma_cos_row.as_mut_ptr().add(x) as *mut [f32; 4])});

gamma_4.store_to(unsafe {&mut *(gamma_row.as_mut_ptr().add(x) as *mut [f32; 4])});

vec_x_4 += dir_dx_x_4; // step the direction vector forward by 4 texels

}

Result: calculating four (cos(θ), γ, cos(γ)) triplets at a time removes another ~1ms, now at ~11ms. Likely this part can be optimized a bit further, but it already feels like a territory of diminishing returns.

V6 – Tone mapping and gamma correction in SIMD

The only scalar part left is processing the HDR output from the Hosek-Wilkie sky model. This stage also needs to be re-written to take 3 per-component arrays and produce a single SDR RGB array. The operation is somewhat awkward – the input data are laid out per component (RRRR… GGGG… BBBB…), while the output must be interleaved per pixel (rgbrgbrgbrgb…). Still, with the help of a few useful ARM64 instructions and LLVM’s excellent backend optimizer, the result is surprisingly good.

Another important ingredient in making this fast is CHEATING:

-

- For skybox rendering, the sRGB transfer function can be simplified to a power function

powf(1.0/2.2)without visually noticeable difference powf(1.0/2.2)is close enough topowf(1.0/2.0), which is justsqrt(), i.e. a single CPU instruction, voila!

- For skybox rendering, the sRGB transfer function can be simplified to a power function

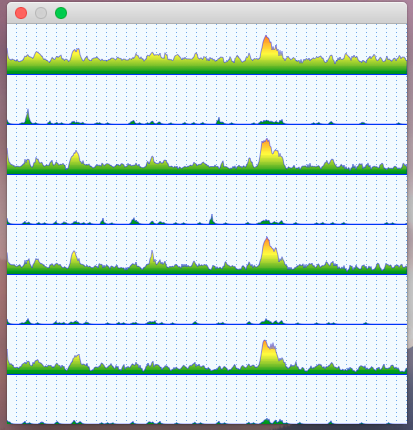

It is also convenient to inject a bit of noise into this post-processing stage to reduce visible banding (before and after debanding):

The combined and SIMDified version of post-processing looks like this:

pub fn map(&self, r: &[f32], g: &[f32], b: &[f32],

texels24: &mut [u8], y: usize) {

let mut r_ptr: *const f32 = r.as_ptr();

let mut g_ptr: *const f32 = g.as_ptr();

let mut b_ptr: *const f32 = b.as_ptr();

let mut output_ptr: *mut u8 = texels24.as_mut_ptr();

let steps: usize = r.len() / 4;

let zero: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(0.0);

let one: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(1.0);

let to_255: F32x4 = F32x4::splat(255.0);

let exposure: F32x4 = self.exposure;

let luma_weights_r: F32x4 = self.luma_weights_r;

let luma_weights_g: F32x4 = self.luma_weights_g;

let luma_weights_b: F32x4 = self.luma_weights_b;

let inv_white_point2: F32x4 = self.inv_white_point2;

let noise_r: F32x4 = F32x4::load(NOISE_TABLE[(y + 0) % 16]);

let noise_g: F32x4 = F32x4::load(NOISE_TABLE[(y + 1) % 16]);

let noise_b: F32x4 = F32x4::load(NOISE_TABLE[(y + 2) % 16]);

for _idx in 0..steps {

// Load inputs in sRGB primaries with a linear gamma ramp

let r: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe { *(r_ptr as *const [f32; 4]) });

let g: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe { *(g_ptr as *const [f32; 4]) });

let b: F32x4 = F32x4::load(unsafe { *(b_ptr as *const [f32; 4]) });

// Expose

let re: F32x4 = r * exposure;

let ge: F32x4 = g * exposure;

let be: F32x4 = b * exposure;

// Calculate luminance: dot(rgb, luma_weights)

let luma: F32x4 = re * luma_weights_r + ge * luma_weights_g + be * luma_weights_b;

// Calculate white scale: (1 + luma / white_point^2) / (1 + luma)

let scale: F32x4 = luma.fma(inv_white_point2, one) / (one + luma);

// Map to SDR

let rt: F32x4 = re * scale;

let gt: F32x4 = ge * scale;

let bt: F32x4 = be * scale;

// Gamma-correction: v = v^(1.0/2.0)

let rc: F32x4 = rt.sqrt();

let gc: F32x4 = gt.sqrt();

let bc: F32x4 = bt.sqrt();

// Apply some noise for dithering

let r_final: F32x4 = rc + noise_r;

let g_final: F32x4 = gc + noise_g;

let b_final: F32x4 = bc + noise_b;

// Clamp the values to [0.0, 1.0] and convert to [0.0, 255.0]

let r_out: F32x4 = r_final.min(one).max(zero) * to_255;

let g_out: F32x4 = g_final.min(one).max(zero) * to_255;

let b_out: F32x4 = b_final.min(one).max(zero) * to_255;

// Convert to integers [0, 255]

let r_u32: [u32; 4] = r_out.to_u32().store();

let g_u32: [u32; 4] = g_out.to_u32().store();

let b_u32: [u32; 4] = b_out.to_u32().store();

// Store the output texels

unsafe {

*output_ptr.add(0) = r_u32[0] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(1) = g_u32[0] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(2) = b_u32[0] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(3) = r_u32[1] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(4) = g_u32[1] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(5) = b_u32[1] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(6) = r_u32[2] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(7) = g_u32[2] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(8) = b_u32[2] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(9) = r_u32[3] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(10) = g_u32[3] as u8;

*output_ptr.add(11) = b_u32[3] as u8;

};

// Advance the input/output pointers

r_ptr = unsafe { r_ptr.add(4) };

g_ptr = unsafe { g_ptr.add(4) };

b_ptr = unsafe { b_ptr.add(4) };

output_ptr = unsafe { output_ptr.add(12) };

}

}Again, the main loop becomes a branchless wall of 4-wide vector operations.

Result: this change pushes the time down to ~4ms. At this point, the Hosek-Wilkie skybox can be regenerated comfortably every frame, allowing smooth real-time Sun movement.

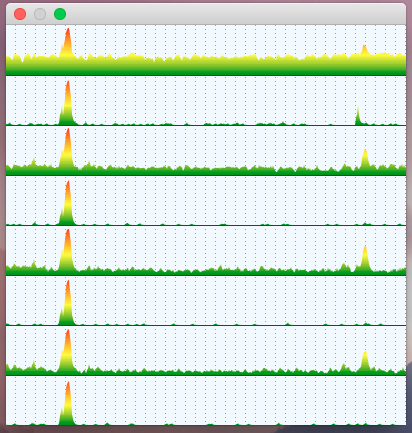

Summary

Overall optimization progress from version to version is summarized in the table below:

| Initial version | ~46ms |

| Less wasteful computation | ~28ms |

| Per-pixel SIMD | ~26ms |

| Per-row SIMD | ~13ms |

| FMA and raw ptr arithmetic | ~12ms |

| (cos(θ), γ, cos(γ)) in SIMD | ~11ms |

| Post-processing in SIMD | ~4ms |

A back-of-the-envelope calculation gives an average wall time of ~8ns to produce each pixel. Considering how much math is being squeezed into these 8 nanoseconds, it’s almost miraculous what modern CPU cores can sustain. Even if my base M1 MacBook is now five years old, it feels that well-written software can run astronomically fast on these machines.

Of course, it’s also tempting to ask: why not just throw a dozen teraflops of GPU compute at this embarrassingly parallel problem and call it a day? Yep, for any practical setting, that likely should be the default approach. But for recreational and educational programming, where’s fun and challenge in that?