Introduction

I have a complicated relationship with website-related technologies. Previously I occasionally had to hack around with various web software, so I got some understanding of how different components work and interact with each other, but generally that’s something I’d prefer to not touch at all. Fiddling with bits & bytes and staring at assembly listings is much closed to me. Unfortunately sometimes one has to deal with it, for instance when developing a software product. In my case, it was Nimble Commander – this app needed at least some presence on the Internet. App Store won’t even accept an application without URLs of general product info, a support page, and a privacy policy page. A combination of NIH syndrome and a finance model of the project left outsourcing this task out of the question, so I had to pick my poison.

The intention was to find a simple WYSIWYG design system that would allow to slam together some content, export it as plain HTML files and then upload them to a server. For such a simple website nothing else was required. However, as it turned out in 2013, this niche was already dead and everything moved into CMS-style systems with backend programming languages, databases, and other cruft. One semi-obvious choice from Apple was its software for simple web design called iWeb. It was already outdated, but seemed to be decent enough for my needs. And so it worked for some time until its age became clear and I had to find something else. After some research, perhaps carried out incompetently, the verdict was to “just use WordPress and don’t reinvent the wheel”. The idea was appealing – a WYSIWYG editor plus a range of various visual themes (both free and paid) with an ability to plug additional components on top. And, when really needed, to fine-tune elements via a custom CSS as a cherry on the cake. Sounds awesome, right?

Not exactly. As it turned out, the built-in flexibility wasn’t that high and the design involved quite a lot of CSS hammering. WordPress was slow as hell and needed echelons of minifiers and caches. The HTML files spat out of the system was an incomprehensible pile of <div>s which made a web browser choke. And, on top of all, at some point, I discovered that the theme referenced some external resources via hardcoded “http://..” paths somewhere deep in its guts, which prevented me from making the website accessible via https. Not that encryption bothered me at all – who really cares about the fact that some person visited a website of a dual-pane file manager for Mac? But in 2018 web-browsers ignited a crusade against non-encrypted internet traffic and Chrome, for instance, started to happily print “not secure” next to the domain name. It was clear that somehow the website had to be moved to https.

There were basically two ways to get there – either hack the existing WordPress instance even further or deploy something fresh. The first option was doable, but was also disgustingly boring and would leave me with even more hacks to maintain. The latter was more time-consuming but at least would provide some new knowledge and entertain a bit.

It should be mentioned that IMHO the current state of the software industry could be fairly described as “dumpster fire” and manifests like this do resonate with me. Having started programming with 8-bit Z80, I’m often quite baffled with how inefficient a certain piece of software must be to perform so slowly on modern hardware. Looking critically at this website, it also appeared to be an over-engineered monstrosity for the tasks it performed. Simplified enough, the website looked like this: MySQL ↔ WordPress(PHP framework, 3rd pty theme, custom CSS hacks) ↔ Minifiers ↔ Caches ↔ Apache ↔ Internet. Since the site contained only ~5 webpages that weren’t changed often, I wondered – why not ditch this cruft altogether and write these pages manually in raw HTML+CSS? Then maybe I could serve 5 static html files without talking to a freaking DATABASE. Surely this area is far away from my usual system programming, but it shouldn’t be that hard. So I decided to conduct an experiment – to rewrite everything from scratch and to measure both how much effort it requires and how much faster the website could be if implemented this way.

Experience

What firstly strikes out is how smooth the web development is. When dealing with C++ it sometimes takes literally hours to just compile the project before you can run anything. Being able to hit Cmd+S in one window and Cmd+R in another to get feedback without a delay does feel like a bliss. When there’s almost no experience in the field (like my case), such frictionless makes the learning process very comfortable.

The combination of HTML5 with CSS3 feels incredibly powerful and intuitive in most cases. There were many instances when I couldn’t believe it – “is that SO easy?”. Perhaps the only case which caused hiccups and had several iterations was the image “gallery”. The problem was to make it lazy loading and somewhat responsive while keeping everything as simple as possible. In the end, the gallery was implemented in ~20 lines of JS code and that’s the only JS code these pages have now.

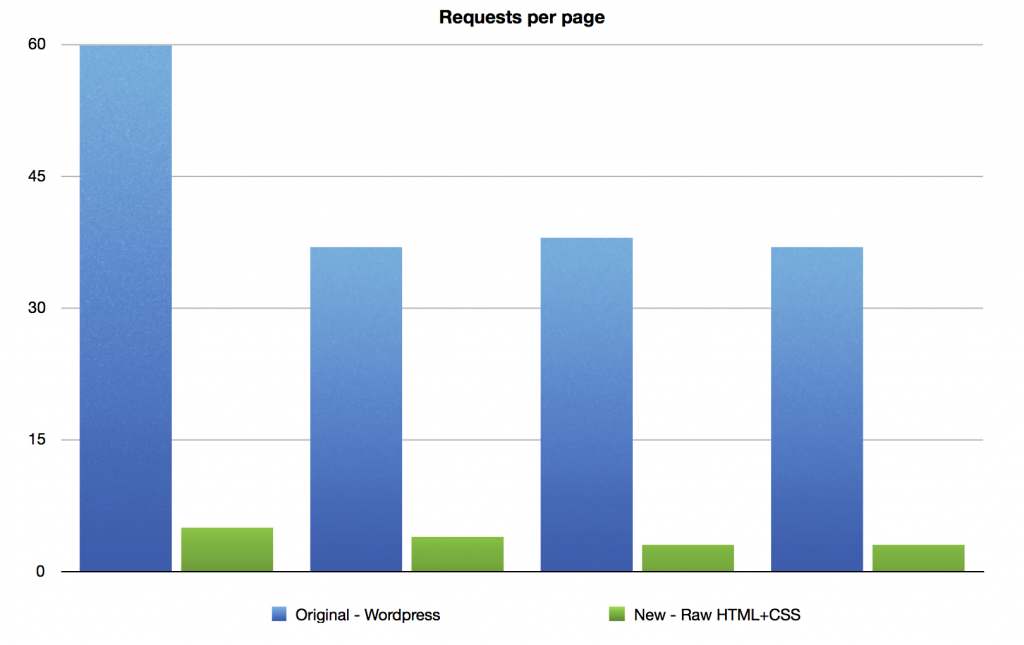

One especially amusing detail was that nowadays it’s often being recommended to combine images into large “sprite sheets“. Haha, with a gamedev background this does immediately ring a bell, though we tended to call them “texture atlases” instead. Good old “trading latency for bandwidth”. Well, that was a no-brainer – easy to implement and provides measurable speed improvement. With this trick, the front page requires only 4 resources to display – an HTML document, a CSS stylesheet, and two images.

It’s hard to tell exactly how much time this rewrite took. The repository with the source files contains 45 commits over three weeks. Assuming the average time spent per day was about 1 hour, this gives a total of ~21 hours or around three full working days. That sounds about right.

In the end, I’ve got something very close to the original design on WordPress, but an order of magnitude simpler and faster at the same time. The result is ~1300LoC in HTML and ~600LoC in CSS.

Data data data

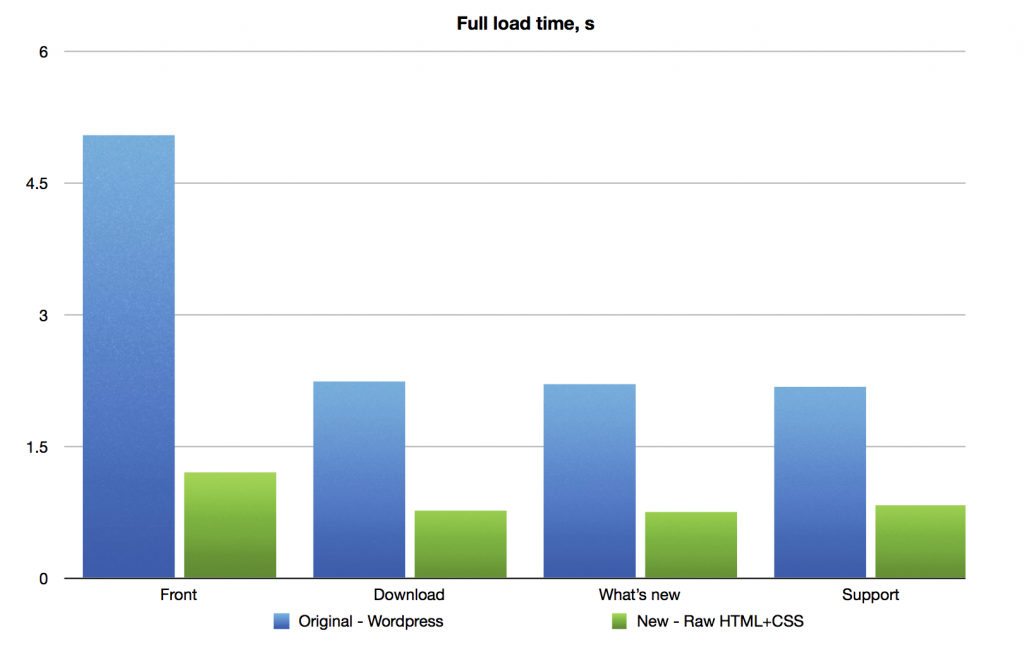

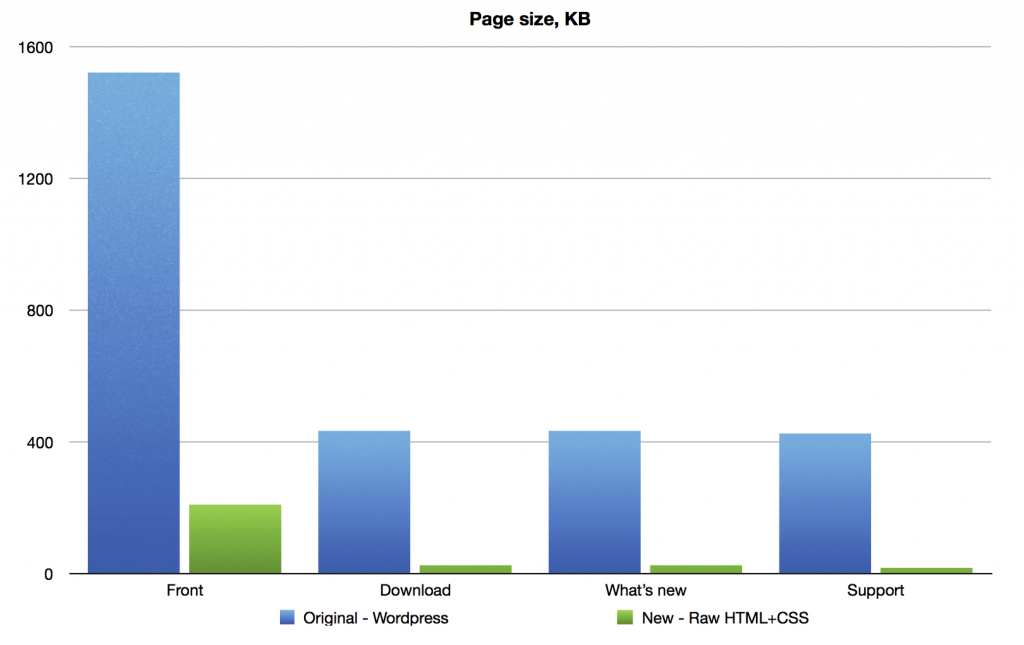

The graphs below show the performance characteristics when accessing the website from London, i.e. doing round trips across Atlantic (the server is located in the NY area). In short: the front page now loads ~4X faster, downloads ~7X fewer bytes and performs 12X fewer requests. To be precise though, it’s kind of comparing apples to oranges, since the original WordPress served unencrypted HTTP, whiles the rewritten site uses HTTPS, which is more complex and requires handshaking, i.e the difference is actually even higher.